Lack of Freedom of Expression and Press Under the Palestinian Authority and HamasSunday 28/08/2016

Assessing the Implementation of the The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights in the West Bank and Gaza -Freedom of Expression and Freedom of the Press

For the full report click, here.

The designated human rights of freedom of expression and freedom of the press, as outlined in the General Comment No. 34 of the Human Rights Committee, contribute to the ideal of a free and open society and “constitute the foundation stone for every free and democratic society.” Both freedoms are limited only along the grounds of hate speech, where an opinion is intended to offend a person or group, or when an opinion calls for action against a person or group. This report examines how Palestinian media and politicians have broadcasted statements and comments that fall into the category of hate speech, specifically rhetoric with clear anti-Semitic or anti-Israel messages.

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) was signed by the PA in July 2014 and contains statutes that promote and defend the liberties of citizens. Article 19 of the ICCPR addresses the freedoms of expression, opinion, and freedom to seek information:

- Everyone shall have the right to hold opinions without interference.

- Everyone shall have the right to freedom of expression…[and includes] freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas…

- The rights above are subject to certain restrictions, but only when necessary: for respect of the right of reputation and for the protection of national security, public order, or public health.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights is designed to be trans-cultural, able to relate to ‘all nations of the Earth.’ It sets an international standard for nations to follow that hold governments accountable for their actions. Like the ICCPR, Article 19 of the Declaration addresses freedom of speech, opinion, and information. Both the Declaration and the ICCPR act to protect basic human rights and freedoms and make clear the importance of freedom of speech and access to information.

Aside from the legally binding documents like the Declaration and the ICCPR, certain non-legally binding measures of support for these freedoms have been adopted. In 1978, UNESCO passed a declaration to protect freedom of expression, speech, and to ban incitement. It is noted that Palestine joined UNESCO in 2011. While UNESCO declarations are not legally binding, they can be considered as soft law, meaning that members are strongly encouraged to comply with the rules and declarations set forth.

In Gaza, under Hamas rule, international declarations and conventions play a lesser role; as the current Hamas government is not recognized as an official state actor by the United Nations, it is unable to ratify international treaties. However, in 2006, Hamas Prime Minister Haniyeh stated Hamas’ “respect for human rights…including the freedom of the press and opinion.” A year later, he reiterated this commitment: “[We Will] respect international law and international humanitarian law insofar as they conform with our character, customs, and original traditions.” For Hamas, though they are not legally bound by international treaties, the Prime Minister’s statements to the international community pledges his support of and adherence to the international standards of human rights.

The West Bank and Gaza draw their legal framework from a variety of legal codes that are both inconsistent with each other, and inconsistently applied throughout different cases, resulting in a complicated understanding of what Palestinian legal standards are. As the PA is a signatory of the ICCPR, it is required to uphold a certain legal standard regarding freedom of speech and expression. Yet, what is taking place on the ground paints a vivid picture of non-compliance with international expectations. In the West Bank, legal codes derive their frameworks from the Ottoman Penal Code of 1916, the Jordanian Penal Code of 1960, Palestinian Basic Law of 2003, and PA Legislation. While protection of freedom of expression exists in Palestinian Law, other laws allot authority to the government to silence the press under ‘correct circumstances.’

Palestinian Basic Law was passed by the Palestinian Legislative Council in 1997 and ratified by former President Yasser Arafat in 2002. It serves as the interim Constitution of Palestine, with two articles (19 and 27) that pertain the protection of freedom of speech. While Article 19 clearly outlines freedom of expression as an inherent right for all Palestinians, Article 27 expounds upon the freedoms and establishment of the press, prohibiting censorship or harassment of the media without legal grounds. However, critics of the Palestinian legal system argue that a lack of clarity in the law allows for government abuses and that the law, in practice, does not provide enough protection for the media. As well, the Press and Publication Law of 1995, also signed by Arafat, stands in direct contradiction to the freedoms outlined in Palestinian Basic Law, specifically in Article 27, which lists a number of restrictions on content that can be published.

The Palestinian Center for Human Rights (PCHR) has criticized the law for the limitations it imposes on journalists. In their report, they explain: “The list of prohibitions includes the publication of everything that contradicts democratic principles and national responsibility, anything against morals, values, and Palestinian traditions and anything that can agitate violence, hatred, and fanaticism. These concepts are elastic and vague and can be misused.” Others have also pointed out the dangers of this law: a 2012 report by the UN Special Rapporteur on freedom of opinion and expression described the law as “excessive government control over the media…”

Under Hamas, the status of freedom of expression in Gaza is worse than what is seen in the West Bank. While the West Bank holds a respect for procedure and formalities in handling legal matters, it is described by witnesses that Hamas authorities act without trials, ignoring all rules. Egyptian Legal Code is applied in Gaza as well as Palestinian Basic Law, with a distinction of de facto Islamization, implemented by Hamas since 2007. This translates to the enforcement of public behavior according to Sharia Law by, what one source has called, the ‘moral police’. Freedom of expression, both in Gaza and the West Bank, is described as “a joke.”

While in the West Bank there is at the very least some legal framework, albeit a failing one, in Gaza sources share that Sharia Law is slowly replacing Palestinian Basic Law. In all, while Palestinian Basic Law does call for a protection of freedom of expression and the press, the complex and unclear legal framework allows for government officials to abuse and overlook the laws.

To ensure a transparent and effective government, the development of professional media and citizen journalism must be encouraged. According to the IREX Media Sustainability Index Report (2011), which assesses freedom of speech, plurality of news sources, and supporting institutions, Palestine scored a 1.75, listing it under the ‘unsustainable mixed system’ category with the likes of Syria, Yemen, and Iraq. For media to be independent, pluralistic, and free, it must be free from governmental, political, or economic control. From 2004, the PA has regulated local radio and television stations under the Resolution of the Council of Ministers No. 182 (2004), granting authority to regulate media to a tripartite committee comprised of the Ministers of Information, Interior, and Telecommunications and Information Technology.

The ministers have the authority to intervene in media content based on concerns for ‘security’; however, they are not subject to any process of checks and balances, allowing them clear control that is not monitored or reviewed by the public or any internal process. In addition, governing authorities in both Gaza and the West Bank have exclusive rights in granting TV and radio licenses, thereby maintaining control in which media can publish information to the public. Unless they receive approval from the tripartite committee, the station cannot publish. The way officials in Gaza and the West Bank regulate audio and visual media stands in direct violation of international standards on freedom of press, as outlined in the ICCPR.

Alongside strict government regulations on media licensing and content, President Abbas maintains complete control over four major Palestinian media outlets, including Voice of Palestine and Palestine TV, both of which run under the umbrella organization Palestinian Broadcasting Corporation (PBC). To work for one of these media outlets, journalists must pledge their loyalty to Fatah, Abbas’ political party. In addition, the PA places numerous news outlets under Abbas’ “intimate patronage,” ensuring that nearly all coverage of news will reflect his policies and the ideologies of his party. In Gaza, Hamas plays a similar role, controlling the main media outlets there, including two newspapers and a satellite TV channel.

Hamas pressures media outlets to adopt their policy lines, quieting any political dissidence. Even private media outlets are subject to government control due to Palestinian journalists often being paid or contracted by the PA. With the government in both the West Bank and Gaza offering preferential treatment to public media outlets (which are more or less controlled by the government), private media is forced to rely on public media outlets for second hand accounts of news stories, severely infringing on the right to access and freely distribute information to the people.

While media in the territories is not under direct and total control of the government, it is severely limited and censored through harassment, threat to a journalist’s job security, and difficulty in finding future employment. These factors discourage political dissent and criticism within private or public media, thereby censoring any political opposition. For foreign journalists, access to information is impeded even more so. Journalists coming into the territories requires a ‘fixer,’ a local Palestinian journalist, to be their translator and protector. There is no autonomy for foreign journalists in the West Bank, and even less in Gaza.

This issue has become so severe that the Foreign Press Association (FPA) released a protest statement in August 2014 calling the practices of the government “blatant, incessant, forceful, and unorthodox.” Journalists out of Gaza share their concerns with publicizing news critical of Hamas. One Spanish journalist reporting out of Gaza in July 2014, when asked why he and his team did not show armed Hamas members, explained: “It’s very simple, we did see Hamas people there launching rockets…but if we ever dare pointing our camera on them [sic] they would simply shoot at us and kill us.” Clearly, foreign journalists often do not feel free, and therefore do not publish wholly truthful or revealing content for fear of backlash, like arrest, physical abuse, the security of their team and any Palestinian associates, or the ability to return in the future.

In order for media to report with true accuracy and transparency, there needs to be an assurance of source confidentiality; when handling sensitive information or topics, both source testimonies can often endanger their safety. While the Press and Publication Law of 1995 Article 4(b) protects the right of the press to keep sources confidential, in practice, this right is not respected by the PA. One source notes that both journalists and sources can be subject to reprisals and that there is no protection for either.

Under the PA, the situation has deteriorated for journalists, with the government going as far as shutting down offices of journalists who voice dissenting opinions of Palestinian leadership. While there is no ‘pre-censorship’ under the PA, many journalists are arrested and imprisoned for months without trial for publishing opinions that go against the PA. This fear imposes a self-censorship by both citizens and journalists alike. If one is targeted for censorship, he endures arrests, detentions (possibly torture), and in some cases can be dismissed from their jobs. This applies to journalists, as well as citizens to attempt to exercise their freedom of expression.

In Gaza, journalists are subject to arrests and beatings without trial. One case is that of radio journalist Yousef Hammad who was beaten by police officers May 2014 because he interviewed civilians protesting the poor quality of life in Gaza. This is only one example of the brutality journalists face to censure their stories and opinions.

Article 19 of the ICCPR is followed by Article 20 of a similar nature, providing a broad standard of international law relating to incitement and propaganda:

- Any propaganda for war shall be prohibited by law

- Any advocacy of national, racial, or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence shall be prohibited by law

Related to Article 19 and 20 of the ICCPR, the PA ratified another international treaty: the International Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD). Articles 1, 4, and 7 urge action to counter discrimination, condemn propaganda, and combat prejudices.

If Article 19 of Palestinian Basic Law is interpreted literally, it would seem that freedom of speech has no bounds, as no article in the legal code bans hate speech. As such, the PA does not comply with the provisions of the ICCPR. Furthermore, based on the wording of Article 22(2) of Palestinian Basic Law, it would seem as though the PA opts to protect martyrs and prisoners of war — despite these martyrs receiving their title for murdering Israeli civilians. Below is one example of legal incitement to violence, with the law serving as incentive to attack Israelis.

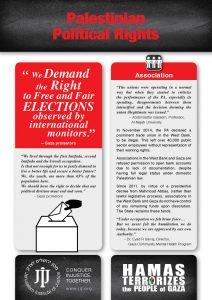

Incitement against Israel and Israelis exists within Palestinian media as well. Israeli cities (in Israel proper) are named as ‘settlements’ in media reports, damages caused by Israel are overstated, and Israel is painted as the enemy of the Palestinian people — in effect, demonizing the state. In the West Bank, outlets like Palestine TV regularly broadcast anti-Israel, anti-Semitic, and anti-Western propaganda, with songs that promote ‘martyrdom’, or violence and death to Israelis. In Gaza, TV programs for children regularly encourage children to commit attacks and die as ‘martyrs’ for the Palestinian cause. On one Hamas channel, a children’s character named ‘Nahul the Bee’ teaches children how to fight against Jews and encourages children to commit acts of violence against them.

Sources explain to JIJ that the PA is not against incitement; however, when it seems Palestinian leadership is making moves to curb incitement, it is because they fear losing donor aid. In an interview on Palestine TV in September 2015, President Abbas himself made calls of incitement by praising “every drop of blood spilled in Jerusalem” as “pure blood… every shaheed (martyr) will be in Heaven and every wounded will get his reward.”

Online platforms like social media are utilized to spread hate and incitement throughout the Palestinian world. Cases in October and November 2015 arose with self-identified UNRWA workers publishing posts encouraging individuals to carry out attacks, with others glorifying terrorists. One poster referred to Jews as “apes and pigs.” Through the official Fatah Facebook page, cartoons were posted in the aftermath of the 2015 Paris attacks blaming Israel for the attacks. When attacks occur against Israelis, like the vehicle attacks on Israelis in the Autumn of 2014 and Spring of 2015, the PA and Fatah fail to condemn the violence; instead, posts surface that encourage and glorify the attacks. In Gaza, Hamas regularly uses their social media platforms to calls for action against “Zionists and infidels.”

In the territories, the freedoms of expression and the press are not truly free; rather, they face severe restrictions and censorship from within Palestinian leadership and society. Both journalists and citizens do not free to speak on topics of politics and corruption, facing consequences like arrest, torture, and career damages. With hate speech, online incitement is not monitored; rather, institutions in many ways work to encourage it. Overall, the current legal framework in the West Bank and Gaza fails to meet the standards set by international human rights law.